Welcome back to the Way of Kings Reread on Tor.com. I’m Carl Engle-Laird, and I’m happy to announce that as of this week, I’ll be joining Michael Pye as a second rereader. This will be my third time reading the novel, and I’ve previously written two articles about spren for Tor.com. From now on Michael and I will be alternating weeks; I’ll cover chapters 5 and 6 this week, and next week we’ll be back to Michael.

These are two exciting chapters for me to begin with, as they introduce some excellent elements to the story. Chapter 5 brings us into contact with Jasnah Kholin, scholar, historian, and atheist, and Chapter 6 introduces Kaladin to Bridge Four, the personal hell that will become his family. The Way of Kings reread index can be found here. For news about Words of Radiance and opinion pieces about the series generally, you can check out the Stormlight Archive index. Now, without further ado, let’s get to the reread!

Chapter 5: Heretic

Setting: The Conclave in Kharbranth

Point of View: Shallan

What Happens

The epigraph presents a grave omen: “I have seen the end, and have heard it named. The Night of Sorrows, the True Desolation. The Everstorm.”

Shallan examines Jasnah Kholin, the woman she has chased across the world and who she hopes will accept her as a ward. She takes note of Jasnah’s unexpected beauty, her regal bearing (“Stormfather! This woman was the sister of a king.”), and the unmistakable jewelry on her wrist: a Soulcaster. Walking with Jasnah is a kind, elderly man who Shallan belatedly realizes must be Tarvangian, the king of Kharbranth. They are discussing some matter having to do with the ardents and the devotaries, and after Jasnah agrees that Taravangian’s terms are agreeable she motions for Shallan to join them.

Although Shallan is worried that Jasnah will be angry with her for being so late, Jasnah says her tardiness was no fault of hers. Instead, she is impressed by Shallan’s tenacity, admitting that she’d “presumed that you’d have given up. Most do so after the first few stops.” The chase was the first of several tests that Jasnah subjects potential wards to, and having passed it, Shallan is allowed to petition.

Jasnah tests Shallan’s command of music (good), languages (passable), and writing (persuasive enough). Shallan’s grasp of logic is less sufficient, as Jasnah rattles off half a dozen logicians that she is not familiar with. Worst of all is her knowledge of history, where Shallan has only a minimal grounding. Shallan tries to defend her ignorance, but is harshly rebuffed, and when they move on to the sciences she loses her temper and mouths off.

Jasnah is less than impressed, and reveals a surprisingly deep understanding of Shallan’s family history. On hearing that her stepmother has recently died, she suggests that Shallan should be with her father, “seeing to his estates and comforting him, rather than wasting my time.” Shallan begins to lose hope, especially when Jasnah reveals that she is the twelfth woman to petition her this year.

At this point their party reaches its destination, a caved-in chamber far underground. Attendants are everywhere, waiting anxiously, and Taravangian reveals that a recent Highstorm had brought down a section of the ceiling, trapping his grand-daughter within. Jasnah prepares to fulfill her end of a bargain with Taravangian by clearing away the caved-in stone, but first asks Shallan how she would ascertain its mass:

Shallan blinked. “Well, I suppose I’d ask His Majesty. His architects have probably calculated it.”

This is clever and concise, and Jasnah recognizes as much, praising her for not wasting time, showing that no verdict has been reached on Shallan’s wardship. She gets the weight from the king, steps up to the stone, and Soulcasts it:

Jasnah’s hand sank into the rock.

The stone vanished.

A burst of dense smoke exploded into the hallway. Enough to blind Shallan; it seemed the output of a thousand fires, and smelled of burned wood.

Soulcasting, dear readers! Having performed this immense magical service, Jasnah calmly returns her attention to Shallan and tells her that she is not going to like what Jasnah has to say. Despite Shallan’s protest that she hasn’t yet demonstrated her artistic talents, Jasnah scoffs. The visual arts are useless and frivolous to her, which is too bad for Shallan, because they’re easily her greatest strength. She decides she cannot accept Shallan, and leaves her behind on her way to the Palanaeum.

Shallan is rocked, but determined. Six months ago, she thinks, she might have given up, but things are different. She follows after Jasnah, determined to become her apprentice:

She would apprentice herself to Jasnah Kholin, scholar, heretic. Not for the education. Not for the prestige. But in order to learn where she kept her Soulcaster.

And then Shallan would steal it.

Quote of the Chapter:

“I have read through the complete works of Tormas, Nashan, Niali the Just, and—of course—Nohadon.”

“Placini?”

Who? “No.”

“Gabrathin, Yustara, Manaline, Syasikk, Shauka-daughter-Hasweth?”

Shallan cringed and shook her head again. That last name was obviously Shin. Did the shin people even have logicmasters? Did Jasnah really expect her wards to have studied such obscure texts?

And just like that Sanderson establishes a deep and rich academic community. Not only is the body of knowledge she expects Shallan to know vast, indicating a long history of academic scholarship, it is international and not limited to the Vorin states. Syasikk sounds like a name from Tashikk, or one of the other nations in that region, Shauka-daughter-Hasweth is definitely Shin, as well as obviously female. I’d really love to know how many of these scholars are women; we discover later that Gabrathin is male, perhaps from a time before men were not allowed to write, so Shauka-daughter-Hasweth is really the only demonstrably female member of this scholarly community. It must be very difficult to write a logical treatise by dictation, so I assume that most logicmasters are female now.

Commentary:

Jasnah Kholin: Princess, scholar, heretic. This chapter only gives us a brief look at who she is, but it still reveals a lot of her personality. Her requirements for pupils are exacting and she doesn’t suffer fools. She’s rather stiff and doesn’t really brook humor or attempts to lighten the mood, much less whining, unfortunately for Shallan. That being said, she’s always willing to praise Shallan when she actually deserves it, which I think we need as an audience. Her praise, because it is rare, is very potent, and has a big impact on Shallan. She has to earn it, which makes us enjoy it more, and respect her more. During my first read-through I found Jasnah to be a very welcome opposition to Shallan. It’s nice for your viewpoint not to always be the smartest person in the room

The relationship that will emerge between Shallan and Jasnah is going to be rocky, but very interesting and rewarding, although I think we should wait to delve into it until it’s begun to unfold a bit more. At this point Jasnah is still a rather mysterious figure. Why is she a heretic? What does that even mean? And how did she get that magical Soulcaster?

Speaking of Soulcasters! They are a truly fascinating magical technology. Soulcasters, or at least major Soulcasters, can turn anything into anything else. The limiting factor that keeps this from being totally, ridiculously overpowered are gemstones, which can be burned out through strenuous use. That being said, the ability to turn rocks into smoke, or food, or gold, or anything else you can imagine, is a pretty wonderful thing for a society to have access to.

Jasnah’s tests show us much more concretely what count as “feminine arts” in Vorin culture. Women are expected to be masters of mathematics, logic, art, history, music, and science, to be able to speak and write persuasively, to balance budgets, and above all to think critically. It’s not just scribing, but also scholarship that is woman’s work. Men handle money, and hit things with sticks and stick-shaped objects, while giving over all intellectual activity to women. There’s a definite power imbalance between the genders, with both sides having very different but very significant realms of influence. I’m going to be keeping a close eye on how Vorinism constructs gender roles and how those roles are viewed by various characters and societies as we go forward. I look forward to discussing debating the issue with all of you in the comments.

This chapter also introduces Taravangian, the kindly old king with the terrible secret. He doesn’t do very much here. He dodders down a hallway, strikes a bargain with Jasnah, and displays concern for his granddaughter. There is one moment, however, that hints at his greater influence; when Jasnah worries that the ardents have a lot of influence in Kharbranth, he confidently assures her that they will be no issue. He’s not always so confident, so I’d consider this to be something of a tell. That being said, we’ll later see that the devotaries are mostly toothless, and normally wouldn’t pose a threat to civil authorities anyway.

The epigraph for this chapter names what I assume will be our final confrontation with all bad things: The Night of Sorrows, The True Desolation, The Everstorm. This is an extremely intimidating message, and there’s a lot to unpack from these names. I don’t know what to think about the Night of Sorrows, although creatures of the night feature prominently in Dalinar’s highstorm dreams. The True Desolation is a little more transparent; now that the Heralds have abandoned the fight, the upcoming Desolation will be a final confrontation, a climactic and decisive battle. And, finally… the Everstorm. A Highstorm that lasts forever? That’s certainly an ominous message.

And, finally, the chapter ends with the revelation of Shallan’s true mission: to find and steal Jasnah’s Soulcaster. Our wonderful, witty young woman, a thief? A deceiver? Who would have thought she had it in her? This unexpected motivation is a great starting point to build contradictions into her character, and will be at the root of all of her most interesting personal developments for the rest of the book.

Chapter 6: Bridge Four

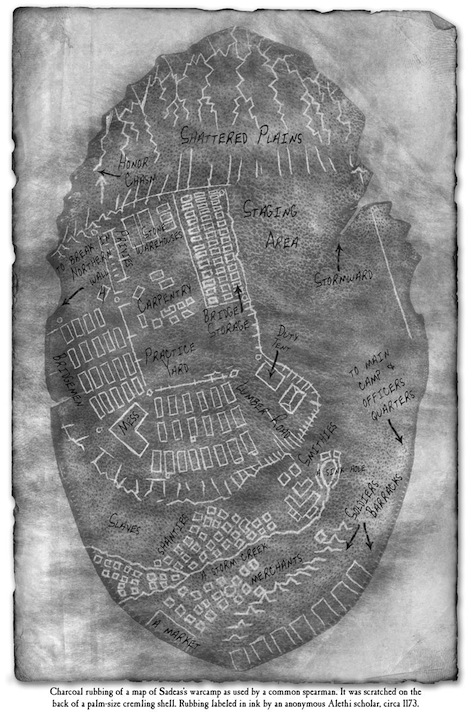

Setting: The Shattered Plains

Point of View: Kaladin

What Happens

At the Shattered Plains warcamp, Tvlakv releases Kaladin and his fellow slaves from the cages so that they can be presented to a female lighteyes. The warcamp is large, and well-settled, filled with signs of long occupation. It’s also full of disorderly-looking soldiers, with unruly uniforms. Kaladin is disappointed by the force he hoped to join, but decided that even if it’s not what he hoped it would be, fighting for that army could give him something to live for.

The lighteyes approaches and barters with Tvlakv over the price of the slaves. She singles Kaladin out, noticing that he “is far better stock than the others,” and has him remove his shirt so she can examine the goods. By his scars she presumes him to be a military man, and he confirms this, then spins a lie about how he earned his shash glyph; he claims to have gotten drunk and killed a man.

Tvlakv steps forward and gives the lighteyes the truth, telling her that Kaladin is a deserter and leader of rebellions. He says she cannot trust him with a weapon, and that he fears Kaladin might have corrupted the rest of his stock with talk of escape. She buys them all up anyway as a reward for his honesty, commenting that “we need some new bridgemen.”

Before he’s led away, Tvlakv apologizes to Kaladin, but this doesn’t go far with him. The lighteyes orders her guards to tell someone named Gaz that Kaladin “is to be given special treatment.” Kaladin is brought through the camp, where he sees the banner of Highprince Sadeas, ruler of his home district, as well as a number of children, camp followers, and parshmen.

Finally, Kaladin finds himself presented to a one-eyed sergeant named Gaz. After Gaz laments that the new slaves will “barely stop an arrow” and treats Kaladin to some petty verbal abuse, a horn blows, and the camp springs into action. Kaladin is assigned to Bridge Four, and made to carry a massive wooden bridge, “about thirty feet long, eight feet wide,” on his shoulders. He has not been assigned the leather vest and sandals that the other bridgemen wear as a kind of pathetic uniform.

The bridges begin running across the Shattered Plains, the army behind them, spurred on by Gaz and other sergeants. The weight presses down on Kaladin, and the wooden supports bite deeply into his shoulders. He soon finds himself tripping on rockbuds underfoot and gasping to catch his breath. A leather-faced man working the bridge near him gives him advice, telling him to focus on counting his steps, and Kaladin manages to trudge on for a long time. After over an hour, they reach a chasm, drop the bridge, and push it across, then collapse to the ground as the army passes over. Kaladin watches a man in red Shardplate ride a horse across the bridge at the center of the army, and wonders aloud if he’s the king.

The leathery bridgeman laughed tiredly. “We could only wish.”

Kaladin turned toward him, frowning.

“If that were the king,” the bridgeman said, “then that would mean we were in Brightlord Dalinar’s army.”

After a brief break Kaladin mutters that he’d be glad to get back, but his leathery friend corrects him. They aren’t anywhere near their destination, and Kaladin should be glad of that. “Arriving is the worst part.”

The bridgemen cross the bridge, pull it up, and jog across the plateau to the next crossing point. They lower the bridge, and the army crosses. This goes on a dozen times or more, becoming a mechanistic routine, until Gaz issues an unfamiliar command: “Switch!”

Kaladin is pushed from the back of the bridge to the front, switching places with those who had been in the lead. As they jog towards the last chasm, Kaladin begins to realize how this new position, with its fresh air and clear line of view, is actually a curse in disguise. The Parshendi are waiting ahead of them, and they have bows trained on the bridges.

The Parshendi fire on the bridgemen, and Kaladin’s friend dies immediately. Arrows fall all around him, killing many at the front of the bridge. Kaladin is grazed, but not badly hurt, and he and Bridge Four manage to place their bridge before he falls unconscious.

His windspren wakes him from his stupor, despite his desire to slip away and not return, by giving him a brief, energetic slap. This saves his life, as the army would have left him behind otherwise. He asks the spren’s name, and she replies that she is Sylphrena, and has no idea why she has a name. She even has a nickname, Syl.

On the plateau across from them Kaladin sees a hacked-open chrysalis with slimy innards, but he has little time to examine it, as he harvests his dead friend’s vest and sandals, as well as his shirt.

Gaz sees him, and tells him to get back to carrying the bridge, clearly upset. Kaladin realizes that he was supposed to die. As he takes the bridge slowly back to the warcamp, he realizes that when he thought he’d reached rock bottom before, he was wrong.

There had been something more they could do to him. One final torment the world had reserved just for Kaladin.

And it was called Bridge Four.

Quote of the Chapter:

He was growing delirious. Feet, running. One, two, one, two, one, two

“Stop!”

He stopped.

“Lift!”

He raised his hands up.

“Drop!”

He stepped back, then lowered the bridge.

“Push!”

He pushed the bridge.

Die.

That last command was his own, added each time.

It’s amazing how fast this torment reduces Kaladin, a sensitive, thoughtful man, into a machine for lifting bridges and feeling pain.

Commentary:

Welcome to the Shattered Plains, where the bridges are heavy and lives don’t matter.

We’re getting closer to the bottom of Kaladin’s arc. He’s reached hell, but it’s going to take more time swimming in the fire lake before he’s actually as low as he can go. Even after this chapter, in which he revitalizes his dream of fighting in the army and then has it snatched away AGAIN, has to carry a bridge with no protection and no armor for miles and miles, and loses a friend within one day of meeting him without even learning his name, there are still worse things in store. I can’t wait to see them again.

The bridge system is the kind of atrocity that you wish only existed in fiction. It is designed purposefully to grind down human lives and transform people into ablative armor. Someday Sadeas will hopefully pay the price for inventing this terrible system, but that day may be a long time coming.

Although Kaladin is now in position in Bridge Four, he isn’t actually part of the group that will give that name meaning for us. None of the people who he will come to care about have made it to Bridge Four yet. We’ll be seeing them soon.

We learn more about Syl in this chapter. We learn her name, her nickname, we realize that she already had that name and has just remembered it, and we see her slap the sense back into Kaladin, literally. This is one of many times when Syl will pull Kaladin back from the brink of death.

We also see fearspren and anticipationspren in this chapter. Both of these spren are relatively straightforward, so I won’t talk much about them. A lot of intense emotions get stirred up in battle, and that attracts spren like moths to flame.

Something I never noticed before is that, during the charge, leather-face invokes “Talenelat’Elin, bearer of all agonies.” Bearer of all agonies is a remarkably accurate epithet for Taln. Why would they believe that the Heralds won the last Desolation, but still have a legend of Taln bearing all the suffering of all the Heralds who abandoned him?

Gaz is an incredibly hateful character. He is bitter, suspicious, petty, and cruel, and he would rather hurt those below him than take steps that could lead to his own promotion. As we’ll learn later, he’s also very greedy, and more than a little corrupt. Kaladin recognizes his leadership style immediately, and disdains it. What Kaladin respects and does not respect about others’ methods of leading, of organizing a military contingent, is an excellent metric for what we should appreciate. Sanderson has positioned him to be the last word in personal, caring leadership, a natural manager who really feels his subordinates’ pains, and gives him plenty of worse leaders for an enlightening contrast.

What I find most impressive about this chapter is the frame that Kaladin’s ignorance gives the war against the Parshendi. Kaladin doesn’t know anything about chasmfiends, gemhearts, or Highprince politics. He doesn’t know why Sadeas has pushed his people so hard to be faster in exchange for bridgeman safety. He doesn’t even realize that bridgemen aren’t supposed to survive. Every aspect of the bridge system is mysterious to him, and therefore seems to him, and to us, nonsensically cruel and wasteful. If we had seen the war from Dalinar’s eyes first, instead of Kaladin’s, it would have been a very different picture. Dalinar knows the whole situation. He sees why his fellow Highprinces push themselves for ever greater speed, understands Alethi competitiveness, and, although he despises Sadeas’ bridge crews, he recognizes them as a conscious trade-off. Kaladin’s unfamiliar viewpoint lets us be shocked, confused, and disgusted along with him, as we struggle alongside him to determine how the bridges could be anything but a senseless waste of life.

It’s also impressive how Kaladin still manages to be impressed by the disorderly nature of Sadeas’ warcamp. I guess that he and Dalinar would agree that a messy camp indicates a dishonorable commander. I hope that’s not a real principle, because I tend to value honor and the tidiness of my desk on entirely different scales.

That’s it for this week! Next week Michael will be back, but I look forward to talking with you in the comments, and will have another reread post for you two weeks from now.

Carl Engle-Laird is the production assistant for Tor.com. You can find him on Twitter.

Good summary, but Tvlakv did not give the real truth. Kaladin never deserted.

Quick note, IIRC: the “truth” that Tvlkv steps in with is not the Truth of the matter. It’s somewhat ironic that both Kaladin and Tvlkv give a truth mixed with a lie: Kaladin really did kill a man that earned him the brand (Veden Shardbearer), and added the lie that he was drunk while doing so. Tvlkv gave a truth (Kaladin led rebellions as a slave) but added that he was a deserter. Kaladin was never a deserter. The ‘truth’ of the brighteyes (i.e. the lies that Amaram told) is the ‘truth’ that matters though…

ETA: AhoyMatey- those are some good thoughts! ;)

Kaladin couldn’t get away with telling “the whole truth”; that the man he killed was an enemy of his army, and that in refusing the spoils his Brightlord decided to take them himself and leave no witnesses, only sparing Kaladin because the event saved Amaram’s life.

Who would believe such a thing? Better to say you lost control in a drunken stupor and accidentally killed someone.

@1 & 2: Yes, you’re of course right. Tvlakv is delivering what he sees as the truth, since that’s the official story he received. Good catch.

Sanderson, in my opinion, is rather good at throwing unforeseen twists at the reader, and Shallan is an excellent example of that. When I got to the end of the chapter and it stated she was going to steal Jasnah’s soulcaster, I was like “Oh. I guess I need to reassess Shallan’s character now.”

Of course, it didn’t stop there.

I find it interesting that while current society does not know that 9 of the Heralds abandoned their Oathpact, it is Taln (the one Herald still subject [albeit not necessarily by choice] to the Oathpact) who bears the monicker of “Bearer of all Agonies.” This would hint that at some time in the past, certain individuals knew the truth of the Heralds’ actions.

It is possible as part of their guilt for abandoning Taln and the Oathpact, one or more of the Heralds kept the aspect of Taln as a “bearer of all agonies” alive.

One (of the many) reasons I like Shallon is that she can think quickly on her feet (a trait that I lack but which I wish I had).

Thanks for reading my musings,

AndrewB

(aka the musespren)

One thing I’ve always been confused about in this chapter is the woman who sends him to bridge four, she is identified as Brightness Hashal by the soldier that hands them off to Gaz. Is she the same Hashal that takes over the running of the bridge crews after Lamaril?

Neither she nor Kaladin seem to remember having met before and the way she is introduced seems to imply she as a new character as well.

I would imagine at least some of the “logic masters” are male and some female.

Remember the ardents in Vorinism are allowed to learn to read and write even if they are male as well as eat “feminine” foods such as jam (I mean really, even the foods are segregated by gender in this religion?).

It’s too soon to tell for sure, but I’m reasonably sure that there is a noted imbalance in the segregation of roles as well. While the only women we really see don’t seem interested in the masculine arts, there doesn’t seem to be any ardent equivilent role either that would allow them to enter into them regardless.

There is also the fact that Vorinism appears to favor male monarchies. Elhokar’s mother is a competent woman and so is his sister, but it’s him sitting on the throne.

One thing I’ve always been confused about in this chapter is the woman who sends him to bridge four, she is identified as Brightness Hashal by the soldier that hands them off to Gaz. Is she the same Hashal that takes over the running of the bridge crews after Lamaril?

Neither she nor Kaladin seem to remember having met before and the way she is introduced seems to imply she as a new character as well.

Dang it! This gosh darned computer caused a double posting. Whoopsy daisies. Editing number two into this apology.

The herald icons for chapter 5 are Palah-Palah. These seem to have reference to Jasnah’s scholarship.

The herald icons for chapter 6 are Tanat-Tanat, which seem to have reference to Kaladin’s assignment to the army and Bridge 4.

I think that Kaladin’s objection to Sadea’s warcamp is not that he’s dishonorable, it’s that they are signs that he is sloppy and careless, without the attention to details of military discipline, supply, cleanliness, and especially the care of the men under his command. A scholar may be able to afford the luxury of being cluttered and disorderly in a single-minded focus on his academic pursuits (although the time wasted in looking for stuff is an impediment there, too). A military commander who desires a well-disciplined army cannot. His men will either follow his bad example, or resent his commands if he is allowed to be sloppy and they are not.

Interesting thoughts about “Bearer of All Agonies” (yes, I think this implies some truths that used to be known about the Heralds have been lost from the mainstream religion … although it’s possible that Taln had this title even when the other nine Heralds still fought beside him. Kalak mentions that Taln always had a tendancy to die heroically).

Also, good insight about how Syl reveals to us that she has a past. And speculations about the names of the Last Desolation. I think saying Dalinar “understands the whole picture” of the Shattered Plains War is gravely inaccurate, though … and by the end of the book, Dalinar would agree. :) The Parshendi’s real origin and motivations are far beyond his understanding. But yes, he understands a whole lot more than Kaladin (or really, anyone else on the Alethi side).

@8: Good point that male Vorin scholars aren’t really an oddity, as long as they’re also Ardents.

The topic that intrigues me most in these discussions, however, is Gaz. And his corruption. Why DOES he have to bribe Lamaril? And what happens to him when he disappears abruptly, later in the book? Personally, I’m hoping he’s tangled up in the covert society of the Ghostbloods. That could give him a lot of potential as an ongoing antagonist.

Thanks, Carl. And I think I’m going to like this tag-team effort between you and Michael.

Love the “feminine arts” in Vorin culture. I appreciate that Brandon once again doesn’t follow the traditional epic fantasy tropes of pre-industrial societies where the women may be the healers/nurturers, but don’t always come across as the most educated. It was great to see Brandon turn “traditional” gender roles on their head in Roshar, where the sciences, math, logic, accounting are all considered “feminine.”

There is still a gender divide of roles, though, so this world (or culture, at least) isn’t too radical from what the traditional fantasy reader is familiar with (or with what history has taught us of most cultures). Warfare is for the men. Scholarship is indeed women’s work. Nice ways of putting it, Carl.

Jasnah is not the typical fantasy-trope-princess that the reader may have been expecting. The reader is shown early on that she is regal, intelligent, demanding yet fair and doesn’t suffer fools. Different from your typical fantasy princess (either kind, supportive and nurturing; or bratty, spoiled, yet with a heart of gold).

Also, I think it was interesting how Shallan characterizes Jasnah once she completes her soulcasting of the boulder.

Could this be an indication that Jasnah had to travel to Shadesmar to soulcast the rock?

I’m still not a big fan of Kaladin’s arc early on in the book. Suffice it to say that Brandon does an excellent job of writing the low that Kaladin drops to and the suffering that he endures, because I really get no pleasure out of reading it.

It is an excellent way of presenting the horrors of this war, as opposed to a more valiant (or at least more palatable) view of war that we often see in fantasy, when viewing the exploits of our main character in battle. That does indeed come later, and the reader definitely has earned the right to read about Kaladin being a badass after suffering through all of Kaladin’s trials and tribulations.

Good comments about Syl, by the way. She does, at times, function as Kaladin’s protector and/or savior. I still don’t think we’ve found out the catalyst as to why one spren singled out one Alethi boy/man and decided (after watching him for a while) that she would bond with him. After centuries of there being no record (that the reader knows of, anyway) of this happening? There has to be more to this, right?

wcarter@8 – That is a good point about the ardents. They are exempt from a fair number of the gender exclusive roles/acts/responsibilities. But they do still seem to have a bias that favors the male. There’s probably more to being an ardent then we have been shown, as well.

“There’s a definite power imbalance between the genders, with both sides having very different but very significant realms of influence.”

Would you say that men and women have equal powers in Vorinism? It seems to me that women have the upper hand, but are still subordinate to men. Women control all the information: financial transactions, histories, written communications, yet the men are the ones in charge. It will be interesting how Jasnah interacts with her countrymen and culture when she arrives on the Shatterd Plains.

@14 Giovanotto

You have an excellent point. While men have the political power, women would have all of the practical power if not for the male ardents.

We don’t know what percentage of the male population are ardents (or what the gender breakdown is within the order itself) but women for all intents and purposes actually control well…everything.

Without them, there would be no economy and no researchable history in the Vorin influenced states.

In fact, if the Alethi culture wasn’t so focused on fighting and competition, I don’t think men outside the Ardentia would have any real power there at all (puppets on thrones who make decisions based entirely on whatever their wives/sisters/mothers tell them don’t count).

I look forward to finding out more about Vorinism, and especially why the gender roles are so stark and all-encompassing.

First things first – Carl, I enjoyed the write-up very much. Thanks!

Odd musings: What does a left-handed Vorin woman do? Learn to function right-handed? Talk about stigma associated with something you can’t help…

How did I never notice this before? “Your demands are about as reasonable as the ones made of the Ten Heralds on Proving Day!” Was that the day they signed on to the Oathpact? And what more does she/do they know about the Oathpact??

Really enjoying (though what this says about me is uncertain) watching Shallan’s assumptions falling to pieces left and right: about Jasnah, life, the universe and everything. What is a heretic like? What is an unmarried princess like? Do people avoid her? What does she expect of a ward? And so much more. On the one hand, I feel sorry for her, having so many expectations blown away in a single conversation; on the other hand, knowing she’ll handle it in the end, it’s rather fun to watch.

Jasnah closed her eyes to do the Soulcasting. Did she send her mind to Shadesmar?

And like you all, I loved the twist to Shallan’s character that we get slipped in at the end of the chapter: that she’s doing all this with the sole intent of stealing the Soulcaster. There’s far more to this girl than the young innocent we see at first – but at the same time, in many ways she is a young innocent. A lovely, complex character.

“Talenelat’Elin, bearer of all agonies” – Profound indeed. As to why they would have both legends (the Heralds won, and Taln bears all the agonies), my best guess is that, just as the Heralds plan to “tell them that we won,” one or more of the Heralds let slip at least the truth about Taln. It may not be as widespread or popular a legend, but clearly it’s about. These things have a way – and oddly enough, people have a way of accepting both, when they’re far enough back to be mythological, without questioning the apparent contradiction. It also ties back to my earlier observation re: Shallan’s “Proving Day” thought. Apparently something is known about the Oathpact…

wcarter @8 – It’s really fascinating to see the different gender roles/rules Sanderson has set up, isn’t it? Thanks for reminding me of it each week. ;) You’re right, though; men can become ardents and thereby be allowed to follow pursuits normally reserved for women – scholarship, engineering, etc. – but there doesn’t seem to be (so far) much interest in going the other way. Then again, maybe there aren’t many women who feel any particular urge to play with sticks and stones? It’s not like they’re normally very restricted in the things they can do, as long as it can be done one-handed.

ChocolateRob @9 – I’m guessing it’s a continuity error. Will check other sources to confirm later, if no one beats me to it.

Confutus @11 – Nothing to add but wholehearted agreement!

And… I see there are more comments now, but I’ll have to finish later. Back in an hour or so! :) (Also – apologies for the failure to proofread and the subsequent sentence fragments…)

One thing I wonder about the bridge crews, that doesn’t get satisfactorily answered:

We’re told that the Parshendi concentrate on the bridge crews even though doing so doesn’t help their chances in battle. The Alethi put that down to them being easily-distracted primitives. For my part, I wonder: is there something the Parshendi really want, and does concentrating on the bridge crews at the expense of the warriors help them get it?

@wetlander

I’m left handed, and I can tell you the modern real world is inconvenient enough for us already whether you’re male or female.

On an interesting side note, one thing I did learn a few years back is there is no such thing as “pure” left handedness. Rather we “lefties” all lie on a spectrum of ambidexterity (the same is not necessarily true for right handed people).

An easy example is my sister. She is also left handed, but can more easily use her right hand for tasks if her left gets tired than I can. However, even I find it easy to use a mouse or pair of scissors my right hand.

@9: It doesn’t sound like a continuity error to me. If Hashal is in charge of buying the slaves, it would make sense that she be the one to oversee the bridgecrews (who are mostly slaves) after Lamaril is disposed of. She’s obviously higher up on the command chain than Lamaril, so after Lamaril’s “screw-up”, she decided that she needed to keep closer eye on the bridgecrews.

As for them not recognizing each other? Why should they? They only met once. Kaladin was but one of probably thousands of slaves that she sends to their doom in the bridgecrews. Sure the “shash” mark is interesting, but the nature of bridgecrews being what they are, she wouldn’t have expected Kaladin to last as long as he did, so had no reason to remember him. As far as Kaladin goes, again, he only saw Hashal the once, and had more immediate and convenient focii for his anger (Gaz and Sadeas, respectively).

Re female vs. male power: Women have almost-total control of the production and transmission of culture, history, etc. (the ardents are, of course, a balance on this, but since male ardents are in various ways symbolically emasculated, it’s a little tricky.) I don’t think it’s totally right to say that gives them more power than men. Men not only control the military, they also have authority over all geopolitical situations, and also authority over all actual financial decisions, even though women do the bookkeeping.

Women could undercut this by misreporting all their commands, in some ways, but male ardents would catch them out pretty quickly, I think.

The stigma of left-handedness is a REALLY interesting question! Noblewomen who are born lefthanded must have really rough lives. From what I understand, though, handedness is something that is partially fluid, and people who might be naturally prone to left-handedness are often trained out of it early in their lives. On the other hand (heh) little girls don’t start wearing longer sleeves until puberty.

Re Jasnah and soulcasting: I think the disorientation and the way she closes her eyes are very strong indications that she’s going to the Shadesmar

Re Talenelat’Elin: If any Herald carried on his legend as the bearer of all agonies, my bet is on Shallash, who is apparently all about honesty. I think that Taln’s symbol on this chapter is linked with suffering.

Re Proving Day: I never associated this with the Oathpact before! Excellent find, and I will have to think about that a lot more.

Great comments, everyone! I’ll be checking in again later.

Oh, additional things, before I forget: Somehow I still didn’t realize that Hashal from later in the book is the same Hashal who purchased him.

Sanderson has hinted that Gaz’s disappearance is something he thinks might cause a huge fan-mystery, similar to the “who killed Asmodean” question. The idea that he was wrapped up in the Ghostbloods is interesting, although I don’t think his one viewpoint chapter works for it. His neuroses tied to his missing eye are veeeery interesting, though. I imagine his debts are related to a number of schemes gone wrong, but possibly there’s something more sinister at work.

@20 I don’t know if it’s suffering per se. Perhaps it’s the endurance through suffering? Kaladin has lost everything, even, almost, the will to live. But not quite. If he had given up entirely, there would have been nothing even Sylphrena could have done. It’s that tiny last scrap of will that makes all the difference and eventually grows into heroism.

I don’t think you can historically state that it would be impossible to write a treatise on logic by dictation. Most ancient Greek and Roman authors wrote by dictation to slaves. The extant works of Aristotle are such a weird mess that they aren’t a good counterexample (they are probably his personal lecture notes, or possibly even notes by an advanced student), but there must have been seminal works of Stoic logic written by dictation. It would be extremely challenging to work out formalized logic if you had some kind of ritual prohibition against even making your own notes or diagrams, of course, but does that absolutely prove that, with a highly oralized mind, it can’t be done?

@23: No, I believe that there would be thinkers who could create logical treatises without being able to write things down. I think there probably are in Alethkar. But between two groups of people, one of which is literate, and one of which is not, I would expect the literate group to produce a higher volume of high-quality logicians and scholars.

I also think that one of the consequences of the stigma against men reading is that readerly pursuits are similarly stigmatized. Men have things read to them, and sometimes memorize passages from the things they have read to them, but I have trouble picturing most of the Alethi brightlords we’ve seen devoting them to writing logical treatises. That kind of thoughtwork seems like it’s been made into an unmasculine calling.

On the subject of Jasnah seeming distant after the casting, as if she was returning from Shadesmar:

Judging from the truthspren demanding real truths out of Shallan in order for Shallen to soulcast the goblet, I think it’s plausible that the entire reason for Jasnah’s scholarly pursuits is so she always has a plethora of truths to tell the spren for whenever she needs to soulcast something. Perhaps those spren are in control of soulcasting and truths are their payment – which is what necessitates going to Shadesmar before you can soulcast.

Shallan’s clever response to Jasnah’s question about the weight of the rock reminded me of my favorite response on the classic building/barometer test question!

For those who haven’t heard this likely apocryphal tale: A freshman physics test asked how you could measure the height of a building using a barometer (the intended answer was to check the difference in air pressure at the base and the roof.) Some students found that too easy and had fun with it, such as the wag who suggested dropping the barometer from the roof and timing its fall – then using the gravitational acceleration formula to solve for the height.

There were a lot of clever answers, but my favorite one was from the student who suggested approaching the building superintendent and offering: “Sir, if you’ll tell me how high the building is, I’ll give you this nice barometer!”

Practical and succinct.

McKayB @12 – Good thoughts. I agree with you that Dalinar doesn’t “understand the whole picture” re: the Parshendi, but he certainly understands the whole picture of how the Alethi are waging this war. Obviously, he’s not inside the mind of the other Highprinces, but he understands the way they function, and the way they treat the whole thing as a competition with each other rather than a war with the Parshendi. Kaladin still thinks they are there for vengeance, and that this is an honorable war. He doesn’t know (yet) how deeply it’s devolved.

Also – cool theory about Gaz being tangled up with the Ghostbloods. IIRC, Brandon gave a RAFO about his fate, so it’s a viable notion. (Of course, with Brandon that could mean anything from “Kaladin will find his dead body next time he does some version of chasm duty” to “he will turn up again in a very unexpected place and screw up something major.” The guy is getting way too good at slippery answers.)

KiManiak @13 – Really, truly, I did write my bit about Jasnah and Shadesmar before you posted this… ;) Great minds, I guess! (But we knew that.)

Giovanotto @14 – FWIW, I don’t really see women as being subordinate to men here. There are certain areas where the simple physical strength gives men a level of “power” over the women in their own household, but in the general functioning of society the women have most of the actual control. I suppose it depends on what you mean by “in charge.” Also, keep in mind that most of what we see from the men’s perspective is in the warcamps, where the men really are in charge of a great deal – warfare being, as noted, “men’s work.” Even so, it’s quite clear that most of the warcamps wouldn’t function well at all without the officers’ wives taking care of all the logistics. And you can see it in the way they’re treated. (Yes, I know there are upcoming situations where women are abused – but that has more to do with social standing than gender.)

We get a tiny bit of female POV in the warcamp from Navani, and we’ll talk about her when we get there, but I don’t get the feeling her frustration has anything to do with being a woman – it’s more the “queen-mum-you’re-useless-now” position that’s driving her nuts. The other main-line female perspectives are all set in Kharbranth (or on a boat), which isn’t as thoroughly Vorin as the Alethi. (The interludes aren’t very Vorin, in general, so those POVs are quite different.)

wcarter @15 – Exactly. All of that. And I do think things will be interesting when we get to see Jasnah and Shallan at the warcamps.

Incidentally, a tiny bit of research/memory reminded me that women can also be ardents. So far, I don’t see a lot of difference except in the acceptable foods; Geranid is still a scholar & mathematician. Oh, and it might answer my question about left-handed women – a woman who is an ardent doesn’t have to cover her safehand. So I guess if you simply cannot function right-handed, you can join the ardentia.

David_Goldfarb @17 – Actually, focusing on the bridge crews does help the Parshendi in the battle; if they can knock out multiple bridges, it creates a bottleneck for the crossing army and makes it harder for the Alethi to establish a front on the fighting plateau.

wcarter @18 – It’s moderately amazing how many things in our world really are more shaped than we realize…

LazerWulf @19 – Looking back through both introductions, it’s certainly possible that Matal & Hashal were moved from the purchasing of slaves to the oversight of bridge crews. We don’t have much info on them, really.

Very interesting thoughts @many re: gender roles. I need to let it stew for a while, but hopefully by tonight I’ll be able to post more thoughts on the subject. One thing I have to say right up front, though: the fact that there are different roles does not necessarily mean that one is inferior to the other. We’ve had this idea shoved down our throats for the last century or so, but it’s not true. “Not the same” =/= “inferior.”

wetlandernw@27- I totally agree with you that men and women can be equal without being identical. I like that in Roshar (and in Brandon’s works in general) women are treated well and shown to be just as intelligent and capable as men (often more so). In the Alethi warcamp this is certainly the case, but women are the bureaucrats while the men make up the government and army. I think Jasnah and Navani have larger roles in government (Dalinar wishes he had Jasnah present to counsel him, I believe) but for most of WoK its the boys making all the decisions.

@25 – Don’t have the text here, but going off of don’t the truthspren say the truth has to be about the person doing the soulcasting? Maybe they should be renamed secretspren to avoid confusion.

Anyway, if I’m remembering that correctly then all the research in the world is useless for soulcasting; it’s all about kind of a meditative self-awareness if you want to do it over and over.

@@@@@ Carl, thank you! I like your review.

Shallan: I like the twist her story took at the end.

Kaldin: Have to say the man is in shape since he survived the first run.

Re: Gaz – he’s a low level dumb thug who was there to 1) Be in Kaladin’s way to begin with, then 2) “allow” Kaladin to change Bridge 4 with permission. Once the changes altered how the bridges worked overall, he got into too much trouble with his superior officers. So he’s either been executed by them, or ran away before they could kill him. If he shows back up in anyway important to the story, I would be very surprised.

Sanderson said this weekend; he learned how to answer fans questions by studying how Robert Jordan did it at interviews and signings. So he’s gotten very slippery.

Re: Safehand – maybe they do allow for lefthanders, we just haven’t encountered one. Had to go to the Coppermind to find out their background, which, I think, is taking an ideal too far, but that happens.

So lefties, have their safe hand be the right. The important thing is that noble women learn to do work just one handed.

Personally I find it an interesting concept, but would want to be lower class in that case. Glove over sleeve hiding my hand.

@@@@@ wcarter – did you delete your post at 8? It’s gone, but the replies all seem reasonable.

Re: Devision of Labor and studies –

Happy to see the girls get to play in more fields, but still think having such a line drawn is a bad thing for a society in general. How the hell could you learn to be a healer without reading?! Or is this stick line just for the nobles? There is oddness; the masses are allowed to be more educated.

Really think the un-married or widowed man is at a major disadvantage. Just think about the store owner we meet in Shallan’s next chapter. What would happen to him if his wife were to die? Does he have to bring in a sister who he hates to run the books? Or hire a woman who could cheat him?

The same problem happens when anyone trust someone with their money, but there is no oversight. Too many people are tempted to cheat the books because they can.

We can even look at Dalinar, he has no wife, no daughters, and no woman he fully trust in his camp.

Food: Would not want to only eat sweet things. And that’s really a mannerism only the nobles could afford. The lower classes, everyone eats the same thing.

@@@@@ 13, KiManiak: I like your thoughts on Jasnah.

@Braid_Tug

That’s weird, I didn’t delete it, and in my browser it’s still there, but post 7 is missing.

I’m not sure what’s going on, but I think it’s some sort of glitch.

I accidently posted this on last weeks re-read. How do people know which Heralds are represented in the beginning of chapters? I feel like there was a whole book about this stuff that I somehow missed lol

@@@@@ wcarter, It’s there now and #7 comes after it. Very strange…

@32 If you look up my comments in particular on the Prologue and Prelude, I explain this. Briefly, it’s based on matching the icons around the border of the first two endpaper illustrations (in the hardback) with the Ars Arcanum in the appendix. I don’t claim originality, another fan on stormlight.com did a lot of work on this, but I’ve picked it up. Hiding clues to things hidden in the story in the icons at the beginning of a chapter was used in the Wheel of Time, and Brandon seems to have adopted the technique, while doing his own twists on it.

I’m not sure that it’s safe to say that only men rule. I recall reading that Elokar’s wife was at home running things with the help of Navani while the men were off playing revenge. What is being the monarch except for being responsible for the paperwork and keeping everything working? Sure, the king would get to do the fighting part, but that kind of demotes him to general rather than a typical king.

The way that they split responsibility makes sense to me. If Dalinar’s flashbacks are correct, then Alethkar is there to protect the world by keeping dicipline and skill at warefare alive even during peaceful times. The only way that they could devote enough people to war would be to have the (usually) strongest people, men, continually practice fighting and have everyone else (women) keep everything running and do everything else needed for survival and thriving of a nation.

Braid_Tug @@@@@ 30

That one was funny. He described it as Robert Jordan being an Aes Sedai, and mentioned it after answering a question of the form “can you tell us about X” with “yes”.

And now to unveil my pet theory re: Syl.

I think Syl chose Kaladin after he refused the shardblade. Considering her apparent revulsion towards the things and the later revelation that she is honorspren, I think it is possible that she considers them cursed since they were left behind by broken oaths, and anyone who touches them is tainted by the broken oath. Of course, the big hole in this is that Kaladin shows signs of knighthood from very early on- his being super depressed and moody as a kid during the Weeping when there were no high storms to charge him is the hint that he was “born this way.” But maybe that wasn’t enough, and to get the whole shebang he needed Syl, and to get her he needed a huge show of honor.

Enjoying the reread!

I wonder if the division of labor has to do with keeping the Alethi interdependent in some ways? So that people overtaken by the Thrill do not end up with unilaterial power to make major decisions. In the past women participated in fighting, and it is hinted that men in other kingdoms read. Also, some of the non-Alethi but Vorin-related/descendent (or maybe just looser/different interpertation of Vorinism) women go without covering their safe-hand, even if such a decision is still new enough to be seen as scandolous by some of the older people. Kind of like a woman wearing a mini-skirt in the early 60’s.

I wonder if the Alethi ever tried something similar to the Hierarchy where they essentially tried to take over, and as a result, were burdened with strict division of labor and a cultural norm of infighting to keep them in check. Even one of Aladin’s short-lived girlfriends being interested in watching fighting is treated as a shock, which means much of the class tasked with logic and administration would be highly ignorant of war tactics. However, the men shown do seem to know enough about administration and operations to see the importance of soul-casters. Which makes me wonder how some things are easily divided. For example, how would The Art Of War be classified by the Alethi? The principles are applicable to other areas than war and can be studied from a philosophical perspective. Also, who would make new weapons or half-shards (discussed later) among the Alethi? They are instruments of fighting but their creation require scientific application (or were they made by ardents?).

Also, I think Gaz getting a POV chapter, him being blackmailed, and his paranoia (even if understandable, but when taken together with everything else) are significant. And it seems Hashal should remember Kaladin as she told Gaz to do something special with him. There seems to be several people, including Laral, who have been instrumental in pushing Kaladin in a certain direction. Wow, I speculate so very much with this book. So very much.

I’m thinking there’s a reason for some of the oddities (from our view) in the male/female roles. Women as scholars and preservers of culture may simply be because, as a culture that pushes men to be soldiers, women are more likely to survive to transmit knowledge.

But, the hand thing is mysterious. In the present, they equate it with modesty. An exposed left hand is indecent. But, they call it the safe hand–and the “ideal” isn’t simply to cover it in a glove but to pretend it doesn’t exist. The implication is that, by covering and hiding it, women are protecting themselves in some way. I would guess it has something to do with soulcasting or a related skill, maybe a forgotten one.

Re: Safehands – Here’s a quotation from Bradon:

There’s more to it than that, but that will stand for now.

Maybe the differences in the male and female culture has some thing to do with the relationship between Cultivation and Honor. The women seem more directed towards cultivating their skills and learning and preparing for the future, whereas manly pursuits seem obsessed with “winning” whether it be in battle or swindling someone out of as much money as possible in commerce and by beating someone they gain honor.

In Japan eating sweets is considered feminine and many men avoid eating sweets in public.

TPoD, ch. 4

TWoK, ch. 5

Jasnah’s “soulcaster” doesn’t work because it is an angreal that channels saidar instead of Stormlight.

re. Gender Roles; Lots of interesting comments about this. I’ve been wondering whether the divide might not be entirely a social construct but actually something fundamental in the nature of Alethi men and women (this would be a bit like in Mistborn where the nobles and skaa turn out to actually be different biologically, not just culturally separate). The reason for this is that the Thrill that Dalinar experiences in battle seems to be far more than just a battle-driven adrenaline rush – there’s obviously something odd about these men that makes them want to fight (influence of Honor/Odium?). In a society where men are pre-programmed to do war, it makes sense that a culture would spring up which supports this. So the existence of the Thrill may well be what underlies the separation of roles.

Does anyone know whether it’s only shardbearers who get this or other men as well? Are any women described as having it? Perhaps men who don’t feel it become ardents…

also, @Wetlandernw Different =/= inferior; completely agree

Wetlandernw@16,27

CarlEngle-Laird@20

Lefthandedness: it’s not that long ago since people were forced (often via slapping) to be right-handed in Ireland (I have a left-handed aunt in her late 50s who was writes with her right hand). In India you eat with your right hand, the left being considered unclean.

In both places and times, lefties had to adjust and I expect the same to be true in this fictional world – if a left-handed person has been prevented from using their left hand from an early age, then they will be able to use their right hand.

I am enjoying this reread and all the comments – thank you all.

(Edit: even though I refreshed the page before writing this, the last comment I saw was 27, which I see has a timestamp from hours ago. Gremlins must be out tiday).

@42 – as a reader of WoT too, (that’s how I found Sanderson, and now prefer him to Jordan, sorry to say) I PMSLd at that connection!

I’m not much of a theorist (I don’t have any), but I LOVE seeing other peoples, and having some of those hidden connections made, that give me that “LIGHT BULB” moment

@PHubbard 43

I believe it’s been stated that the Thrill is in fact from Obium (and thus probably not a good thing).

@helen79

There are stories of it happening in Catholic schools in the U.S. too, though obviously not in quite a while.

We lefties have to learn how to use our right hand for a number of tasks in any case simply because of how many things are set up for right handed people.

My grandfather was left-handed growing up, and he would have his left hand slapped with a ruler if he tried to write left-handed. That must have been fun, haha. I had a stroke when I was two weeks old on my left side. Even though I’m naturally a lefty, I do a lot of stuff like sports with my right hand.

I love the theory about the Weeping and Kaladin. Something I didn’t even think about. I also agree about the shardblades, Syl doesn’t like them because they are “tainted” by a forsaken oath. I’m really curious about what made the Knights Radiant forsake their oaths. Could they have either found out that they were abandoned by the Heralds or felt the same emotions that the Heralds did when they broke the Oathpact?

The weeping theory is quite excellent.

I think that it’s unlikely that most left-handed women would choose to become ardents just because of that. Becoming an ardent is a pretty big deal, since you aren’t allowed to own anything and actually become property yourself

I’m very much enjoying the re-read. Thanks to everyone involved!

It seems to me a thin case to suggest that the decision of the Radiants imparts dishonor to their Shards. I would more readily expect to learn that the source, or Intent, related to how the Blades came to Roshar, is in conflict with that associated with creatures like Syl.

Handedness is sometimes an illusion. Numerous great golfers in history were naturally left-handed, but lefty clubs weren’t mass produced, had to be custom made, so it was mostly expected that golfing was done right-handed. The strange reversal of this is Phil Mickelson, who is naturally right-handed, but was taught to swing as a toddler by his father standing in front of him and having him mirror Dad’s movements, resulting in his swing being left-handed. “Lefty” isn’t a lefty.

birgit @42 – That’s what’s wrong with it! Nice catch. :)

PHubbard @43 – re: the Thrill – I don’t think anyone but shardbearers have talked about it using that word, but think about what happens when Kaladin gets going with a spear. To me, it sounds very similar. That said, we really don’t know much about it. A search through the ebook verifies that Dalinar, Sadeas and Adolin are the only ones who talk about it; they’re all Shardbearers, but they’re also all Alethi males, and warriors. (Actually, they don’t talk about it much, because “one doesn’t” – but Dalinar thinks about it a lot, and has brief conversations with the other two about it.)

One possibility is that those who have the potential (whatever defines it) to become Knights Radiant are also the ones who experience the Thrill. I’m thinking of the part in Chapter 19, where Dalinar is talking to the female KR in one of his visions. She talks about “One kingdom to study the arts of war so that the others might have peace.” She speaks of how those of Alethkar maintain “the terrible arts of killing” and pass them on to others when the Desolations come. But the one I’m really thinking about is this: “Fighting, even this fighting against the Ten Deaths, changes a person. We can teach you so it will not destroy you.” I won’t venture any further into speculation, but I submit that the Thrill might be part of what’s going on here, and that it has morphed somewhat since the Recreance.

helen79 @44 & wcarter @46 – (Mostly OT) It’s not that long ago that left-handedness was somewhat forcefully discouraged in the USA, too. My dad was a natural lefty, but when he went to school he was required to be right-handed. (I don’t know if he was smacked with a ruler for it, though…) He learned; it wasn’t that bad, I guess. The twist on it is that in his early forties, he was in an accident that eventually left his right hand paralyzed, curled halfway between open and fisted. So he had to relearn how to be a lefty again. It worked, after a fashion, but writing has always been difficult for him since then; he had never been allowed to learn to write with his left hand. Fifty years later, he still has to write slowly to be legible. (Well, he doesn’t do much writing any more, but you get my drift.)

wcarter @46 – “I believe it’s been stated that the Thrill is in fact from Obium (and thus probably not a good thing).” It’s been suggested/speculated, but not confirmed that I can find. I don’t personally think it comes from Odium (see previous paragraph ramblings) but I think it has… devolved, maybe, from what it was intended to be. I think the original version was something that aided the KR in their battles against the Voidbringers, the Desolations, whatever was attacking Roshar. In the past 4500 years, without the intended target and with the KR disbanded and no longer training properly as they once did, it doesn’t work quite the way it should. Or perhaps it isn’t being used the way it should.

Carl @48 – re: the Weeping – I live where we have long stretches of clouds & rain, and SAD is a way of life; I just assumed Kaladin reacted the same way to the lack of vitamin D. :)

No, I wouldn’t think that most left-handed women would become ardents; it’s a big commitment. But most left-handed women would be among the lower classes anyway, and they just wear a glove, so left-handedness wouldn’t matter. For those of the upper classes, I expect the majority would learn (like my dad and so many others) to function right-handed. Even though young girls aren’t expected to keep their left hand concealed, I can’t think they’d be allowed to learn to write left-handed, or any of the other things that would be made impossible by a modesty sleeve. It would be a last resort for someone who simply could not function right-handed, and I have no idea how common (or uncommon) that might be.

Loosely related but mostly OT… I came across another WoT tie-in concept that rather jumped out at me while I was researching the Thrill: “To lack feeling is to be dead, but to act on every feeling is to be a child.” Sounds like what a certain someone was trying to teach a certain Dragon Reborn…

I’ve always assumed that it is only Lighteyes that feel the thrill, we are not been told very much about it but they give the impression that it is more common than just in shardbearers.

Not that I have any evidence for it but I’ve always guessed that Odium somehow tainted the Radiants and through them their Blades and that the Lighteyes are all descendants of either them or the soldiers that took up the discarded shards. Light eyes and the Thrill are remnants of his influence.

PS. Is anyone else assuming that Jasnah’s real reason for disregarding the Visual Arts is simply that her own artistic talent is on par with that of Sarene from Elantris (nonexistant). It would undercut her imposing reputation if it were known that she was so bad at one of the womanly virtues so she bluffs through it pretending it is of no importance.

Freelancer@50

Good point about the golfers. As it turns out, a lot of modern golf teachers will tell you that you should actually lead with your dominant hand (i.e. a “right-hander” should play like Phil Mickelson.) Of course you need to start learning that way — although there have been some golfers who have “turned around” (one example that I know of personally is Rod Laver, much better known for his tennis play of course.)

Now for an interesting anecdote: When I was at JCon I did not bring my copy of AMoL to the Rereaders dinner, where so many of us signed each others books. I decided I really wanted my reread friends to sign mine, so I dragged my book around on Saturday, getting various rereaders to sign it (which meant I got to watch each signature being done). I was amazed at how many lefties we have! I should have kept track, but I’d estimate over a third of those who signed my AMoL signed it left-handed.

@52: I assumed it was the thrill that Kaladin felt when he picked up the spear for the first time. It is described in the same way as the Thrill among the lighteyes.

@29 TBGH

If we are going to suggest renaming ‘truthspren’, we might want to try fact-spren or identity-spren. It seems that they are related to what things are and what they change to.

@52 The Thrill seems to be described as a feeling of superiority of yourself over all those around you, the desire to destroy and dominate those who are lesser and reveling the gloriousness of defeating and destroying.

When Kaladin uses the spear it seems to be pride in truly excelling at a skill, feeling born to be able to do something on instinct and reaching your full potential.

The Thrill seems to be about destroying those that are lesser whereas Kaladin’s skill is about pride in yourself and being all that you can. He takes no pride in destroying or dominating despite his ability to do so if needed. Basically there is no hatred in what he feels when he fights.

@52 I don’t get the impression that Jasnah is covering her inability with bluster. She has enough intelligence, focus, and discipline that she could probably become more than merely passable at art…if she had any interest it.

What I see instead is the arrogance of the specialist, one who subconsciously assumes that because a subject is of no value to her, it is of no value at all. Jasnah is by inclination a historian, a philosopher, and a scholar, and the visual arts are not outstandingly useful there. She has probably seldom seen what she considered a non-frivolous use of art. As an atheist, she doesn’t have much use for religious art.

But Shallan uses her art in the service of natural history…a sufficiently non-frivolous study that Jasnah is forced to recognize that her aspiring ward is more than the rural opportunist looking for a free ride to prestige that she took her for. As we will see.

ChocolateRob @56 – I have to firmly disagree with your interpretation of the Thrill. While the battle Thrill definitely involves killing the opponent, I didn’t get any impression of feeling superior to everyone or “destroying the lesser beings.” Dalinar’s Thrill almost always seems (to me) to be much like how you describe Kaladin’s “pride in being all you can” – a fierce joy in the skill, accompanied by some kind of actual boost to his natural skill.

* If you look at the first time we see the Thrill mentioned, it’s the Thrill of contest – which couldn’t possibly have arisen if he considered himself superior “over all those around” (i.e. Elhokar). If there were no real contest, no worthy opponent, there would be no Thrill.

* The next time we see the Thrill mentioned is when Sadeas has been insulting Renarin and Dalinar calls him on it. The Thrill tempts him, because he is angry and would like to settle it by fighting Sadeas, but he resists. It’s more to do with right/wrong than superior/inferior.

* Third time: the vision where Dalinar fights the Midnight Essence creatures. He’s fighting for his life against creatures he’s never seen before, but which could quite clearly rip him to shreds. He uses the Thrill to ignore his own hurts and give him focus, because if he doesn’t take this thing down, the woman and child will die. (No idea what would happen to him if he “died” in a vision, but it felt real enough to him at the time.)

I don’t currently feel a need to go through the whole book to prove the point, but those three, the first ones we see, don’t sound anything like your definition.

Confutus @57 – Well said.

Honorable warriors take no pleasure in killing. Period.

Dailnar becomes beset by an unbearable sadness at the slaughtering of the Parshendi, and it drives away the Thrill. This very connection would be completely unworthy of note if the Thrill were simply some blind rage attained during battle.

forkroot @53

Well, I cannot lay claim to having better understanding than “a lot of modern golf teachers”, but I wholeheartedly disagree. The generation of club-head speed in the swing is entirely from the back hand, which is the dominant hand if someone swings according to their nature. The front hand has the lighter grip, the elbow locked, and sweeps the club into position. The back hand turns over past the front hand at the bottom, accelerating the clubhead through impact, creating power. To this extent, the mechanics of a golf swing are very much like a baseball swing; front hand steers the bat into line with the pitch (up-down/in-out), the back hand punches the bathead through the hitting zone.

About your other point, I would not have been surprised. The dominant hand is commonly understood to be determined by the dominant half of the brain. (Us lefties are the ones in our right mind!) And that being the more creative side, people who gravitate toward the more artistic pursuits tend to be right-brain types, resulting in a larger proportion of left-handers.

I don’t think that women are subordinate to men in this society. There is a line from Dalinar’s POV where he talks about a lighteyes officer is really just half of a functioning pair with his wife, with both partners being equally important in fullfilling thier duties.

I agree with Freelancer. The Thrill is not described as a good thing the more that Dalinar starts following the Codes. I think that is pretty obvious from the text. So would Syl be drawn to Kaladin if he thrived off of that? Probably not from what we know of her so far.

My theory is that the current Shardblades/Shardplate are now tainted and are tools of Odium. We don’t know enough yet to know whether all lighteyes feel the Thrill, but I believe that it might only be a thing that Shardbearers experience. Remember that in Dalinar’s visions, the shardblades/shardplate look different than what current bearers have. Also irc, the “light” goes out of them when the KR drop their burdens. I believe that Odium instills the Thrill through the Shards. There’s a reason that Kaladin and Syl both feel something wrong about them. I can’t wait to learn more and see if this is right or not.

Free@59

Anyone who has seen my golf swing would be skeptical about any assertions I would make! I merely relate what I have been told by several instructors.

—

Another rather curious fact about the rereaders in attendance: Most of us were married, but no spouses were in evidence. (BillinHi’s wife was reportedly there, but was not registered for the convention and we never met her.) I’m curious why the WoT bug doesn’t bite both halves of a marriage more often?

—

Getting back (sort of) to WoK – I was never quite sure what the scene on the cover represented. I had the perfect chance to get it “from the horse’s mouth” so to speak, so I asked Michael Whelan. He explained what he was trying to do with the scene (BTW, extremely cool guy.)

So, it was a good thing I asked, because I was only partially right about the scene. Anyone care to state what they think it is?

forkroot @62 – My best guess was the Parshendi Shardbearer and Dalinar (probably after the battle at the Tower), but I haven’t put a lot of energy into trying to figure it out…

Re: the Thrill – I’ll have to reread more fully all the passages before I can say anything firm, but I will reiterate that my impression is of a good thing gone sideways. The Thrill would be a wonderful thing for a KR fighting the Desolation – the focus, the enhanced skill, the joy in battle… when you’re fighting for the survival of your race on your home planet. When all you have to fight is other people on your own planet, though… it’s gotten twisted. But I’ll go do some further reading and examination of the passages available before I go any farther.

One thing to think about (Freelancer, I’m looking at you…): IRL, the only opponent humans have are other humans, and killing them is not a glorious or joyous thing. It could be said that when it gets to that point, we’ve already failed. But what if the “other” were known creatures of real Evil, creatures whose sole purpose was the extermination or subjugation of all humanity? Would there not be honor, glory, and perhaps even pleasure in destroying such enemies?

@63

Coming from someone who has been to Iraq and lost friends and comrades, no. There should never be pleasure in killing something. Once you cross that line it is a slippery moral gray slope.

War and killing are terrible. If it was an Evil Creature, it would be necessary…but that doesn’t mean you should get pleasure from it. Now I enjoy these types of stories that involve war and fighting because you see things like immense courage.

If you want to read a seriously fantastic book, you should read Once An Eagle by Anton Myrer. He was a marine in World War II and probably wrote the best book I have ever read. Everyone should read that book at least once.

My guess about the cover…Dalinar and Sadeas with the metaphorical gulf between them

reading through this thread after reading this book yet again…@17..

I notice in the Tower battle it refers to the parshendi concentrating their attacks on those more skilled in battle and with fewer wounds (or Lopen who is crippled). That would seem at odds with them concentrating archery on the bridgemen who are generally unarmed non-combatants.

I dont use this much but always like the comentary. I have read this atleast a dozen times, that said . here I go. kalidin as a child was taught that to save people as a surgen was honorablewhich he took into his heart and believed. RE:hie father was the most honorable man that he knew becaus of his life of service to his fellow man. at that time he also was strugling with the concept of can i be honorable as a fighter if i am protecting others. prime example; dalinars vision about hte female KR that fougth and also healed, so kaladin was always being shaped by his honorable nature. kaladin now goins the army to protect his brother and is learning that it is honerable to protect others also.this is what atracted SYL to him in the first place is that kaladins heart is in the kind of place that an honor spren is atracted to.[I think that syl has always been one of these:honor spren:and association is slowly helping her to remberwhat she is and that memory will help everyone to learn what a KR truly is. Now kaladin and his bridge crew are teaching kaladin what the true malning of his nature will be.Isnt it interesting tha this is when he starts to learn about stormlightand when SYL becomes more aware of herself .the poit is that kaladins heart is in the rignt place.

example; whe dalanar is moraly compeled by his heart and the codes that he lives by to protect sadeas frome the parshende and the king from the great shell are when the shard plate sdtarts to glow because dalinaris now being honarable and his heart is in the right place.

question; when wil dalinar get an hohor spren or wil another spren be atached to him and together they will evolve also thus the new beginings ov the new KR?

When shards and plate are used right along with the thrill only then do the become truly powerful.

Q; will kaladin get plate and willSYL only let kaladin have one of the dawn shards. becaus i think that the parshende have the shards and when we get the right people brandon will re interoduse them.

Here is what i think is that with faith and good intentions will be the way the KR will be great protectors and that is what the fenale KR in dalinars dream ment whe she told him that they would show him how to use the thrill and not be destroyed,or be ruined by the baser side of human emoitions.

alright ,the KR gave up their shard plath and blades after the hearlds informed them tha they had won, so the hearlds are gon and the KR were left to their own devices. Then they started to abuse the ,when they realised this they gave up theirplat and blades to other men because they realised that they were no mor worthy than so they disbanded their order just like the hearlds because the war is won what is the point in continueingafter they were dond and so that they would not be the ones to use them in a dishohorable way

RE;Dalaners dreams and i dont rember where but it goes somyhing like this the KE are starting to charge more and more for passage through their relm,thus we see that their was abuse when the war was done by the KR

sorry that this so long and ahs so many errors but i have been thinking about this for a lomg time and just couldent resistany more . I have enjoyed this read and look forward to more.

PS; i was suposed to be left handed and ame way ambidextrous. I write on paper with my rignt hand and on the chalk board with my left, I have a left ahndid wedge ind my golf bag and it has saved my score many times . i use hand tools and power tools whit eather hand well all sports as well but i can only throw a ball with m left hand

I think that syl was always a honoh spren and was waiting for the right circomestances to be met. once she was able to talk to kaladin his transformation was inevitable, he was probably born able to use stormlight but with syl this will be vastly improved. she will also be able to rember more as tim goes on and the bond with the 2 of them grows.

questions:1 will syl beable to rember her past lives or will she grow off the experiances of this .If she rembers enough will it lead to the recreation of a knew raidiant order with dalinar at the head and kaladin as the example to others of how to act.